320H.3 - React Hooks: useState

Learning Objectives

By the end of this lesson, learners will be able to:

- Explain what React hooks are and how they are used.

- Use the

useStatehook to manage local state. - Use updater functions to update state using previous state.

- Use

setfunctions to set state inside of event handlers. - Describe the difference between primitive values and reference types in state.

- Update objects and arrays in state without mutating the state.

- Describe the purpose of the Immer library.

- Use the

useImmerhook to simplify state updates.

CodeSandbox

This lesson uses CodeSandbox as one of its tools.

If you are unfamiliar with CodeSandbox, or need a refresher, please visit our reference page on CodeSandbox for instructions on:

- Creating an Account

- Making a Sandbox

- Navigating your Sandbox

- Submitting a link to your Sandbox to Canvas

React Hooks

Hooks let you use different features from React alongside your components. You can either use the built-in React hooks, or combine them to build your own (which we will discuss how to accomplish in a later lesson).

Here, we'll discuss one of the most commonly used React hooks, useState.

The useState hook is the first of many you will encounter in React. Any function starting with "use" is called a hook, which is a special function only available while React is rendering. They let you "hook into" different React features.

Hooks can only be called at the top level of your components (or your own hooks, which we'll discuss in a later lesson). You cannot call hooks inside of conditional statements, loops, or nested functions. Hooks are functions, but it’s helpful to think of them as unconditional declarations about your component’s needs. You “use” React features at the top of your component similar to how you “import” modules at the top of your file.

The useState Hook

We've discussed the concept of state and what state "is" in the past few lessons. Now, we'll talk about how you can use state within your applications. As with all good semantic coding, React provides an obvious tool for accomplishing this: useState.

The useState hook allows us to generate variables that are special, as updating them will trigger your component and its children to update as well. To illustrate why this is important, let's revisit an earlier example:

In the example above, we've added an additional block of code that changes the value of people[2].name after a delay of one second. You can confirm this has completed by viewing the message logged to the console. Yet, Batman's identity remains a mystery, as nothing changes on the webpage display... why is that?

Despite changing one of the "state" values that originally created our webpage, React doesn't know to update or re-render that section of the page. Local variables don't persist between renders, and changes to local variables won't trigger renders.

That's not very reactive! It's also not how we as developers are supposed to change state in React. This is where the useState hook comes into play, allowing us to set state values that React watches, and modify them in a way that React will... react to.

The first step to using useState is importing the useState hook:

import { useState } from "react"Inside the body of your component function, you can then initiate a state variable. The naming convention is "something" for the variable and "setSomething" for the function that updates the state's value.

For example, if we wanted to create state for a counter application, the state setup would look like this:

// initiate counter at 0, setCounter lets us update the counter

const [counter, setCounter] = useState(0)The value passed to useState is its initial state value, and it returns the state - in this case counter, and a state setting function - setState. Unlike local variables, the state returned from useState persists between renders, and when changed via the setting function, React triggers a new render.

So a simple Counter component would look like this:

import { useState } from "react"

export default function Counter(props) {

// initiate counter at 0, setCounter let's us update the counter

const [counter, setCounter] = useState(0)

// Function to add one to the state

const addOne = () => {

// sets counter to its current value + 1

setCounter(counter + 1)

}

// The h1 displays the counter, and the button runs the addOne() function

return (

<div>

<h1>{counter}</h1>

<button onClick={addOne}>Click Me to Add One</button>

</div>

)

}That's as simple as it gets. What happens when the button is clicked?

setCounteris passed the current value plus one.- React then compares this new value to the old value of

counter. -

If they are the same, React does nothing.

- Beware of references as values when it comes to objects and arrays. Make sure you understand pass by value versus pass by reference.

- If they are different, then React updates its virtual DOM based on a re-render of the component and its children.

- It then compares the virtual DOM to the real browser DOM and only updates the places in which they differ.

The above process is why "state" variables are reactive, meaning the DOM will update when the value updates. All other (non-state) variables are not reactive, and will not trigger updates when changed.

Below is a more sophisticated example from the React documentation that uses the exact same "counter" logic. When the "next" button is clicked, it increments the value of the state variable index, which triggers a re-render. Note that everything that references index is recalculated, which allows us to declare let sculpture = sculptureList[index] once, and just reference sculpture within our return, since its value automatically changes every time index is changed via setIndex.

What happens when we click "next" at the end of the list? How could we add some simple JavaScript to our click handler to fix this?

How easy would it be to add another button labeled "Previous" that moves to the previous element in the sculpture list?

Take a few moments to complete these tasks in the sandbox above.

Passing Updater Functions to setState

If you pass a function to the setState function as an argument, it must be a pure function, take only the pending state as an argument, and return the next state. React will then put the updater function into a queue and re-render the component during the next render. React calculates the next state by applying all queued updaters to the previous state.

We have already seen an example of this with our counter state example above, which uses a reference to the current state to calculate the next state. Since the counter example is so simple, a full function definition is not required. However, these two code blocks are equivalent in behavior (sort of! We'll talk about the key difference in a moment):

const addOne = () => {

setCounter(counter + 1)

}const addOne = () => {

setCounter((counter) => counter + 1)

}In this case, (counter) => counter + 1 is the (anonymous) updater function. By convention, it is common to name the pending state argument using the first letter of the state variable name, so our syntax could be simplified to (c) => c + 1, for example. That being said, you should use whatever convention is appropriate for you and the team you are working with.

The minor but important difference between these two approaches is in how they handle sequential, simultaneous updates. For example, what happens if we do this:

const addOne = () => {

setCounter(counter + 1)

setCounter(counter + 1)

setCounter(counter + 1)

}The result may surprise you. In order to explore this behavior, below is a modified version of the previous sculpture gallery example.

In the modified example, we've added a new button that goes to the sculpture after the next one, and named it "Next++". It calls the nextNextIndex() function, which calls setIndex(index + 1) twice. Obviously, it would be easier to call setIndex(index + 2) once, but we're demonstrating a very specific behavior in this example.

Try clicking "Next" and "Next++" and verifying their behavior.

It seems that nextNextIndex() only increments the index state by one, but how could this be? The setIndex function (and all set functions) does not update the state variable within the code that is already running. We are effectively updating the state to the same value multiple times, because we are not allowing time for the state change to occur.

Using an updater function completely changes this behavior, since the functions are put into a queue and called in order. Once the queue is empty, React stores the final state given by the results of the queued functions.

To demonstrate this, try changing the setIndex calls within nextNextIndex to contain simple updater functions, and note the change in behavior.

Generally, it is always recommended to utilize updater functions when updating state based on previous state, even though it is not always necessary. In a later lesson, we will explore the use of reducer functions to handle state changes for us in a way that scales better.

Immutable State

State in React is immutable; it cannot be changed, only recreated. How then, in the example above, do we set counter to counter + 1? Since counter is just a number, a primitive data type, adding to it creates a new number for React to use. This is generally intuitive behavior, but it means we need to be careful when using reference types like arrays and objects.

If the state is an object or array, make sure you pass a new array or object and do not just modify the old one. Objects and Arrays are reference types, so if you pass the old array with modified values the references will still be equal, so there will be no update to the DOM.

Don't do this:

// modify the existing state

state[0] = 6

// then setState as the existing state, triggering NO update

setState(state)Also don't do this:

// these two variables are both pointing to the same position in memory

const updatedState = state

// no update is triggered

setState(updatedState)Instead, do this:

// create a unique copy of the array

const updatedState = [...state]

// modify the new array

updatedState[0] = 6

// set the State to the updatedArray, DOM will update

setState(updatedState)Aside: Immer

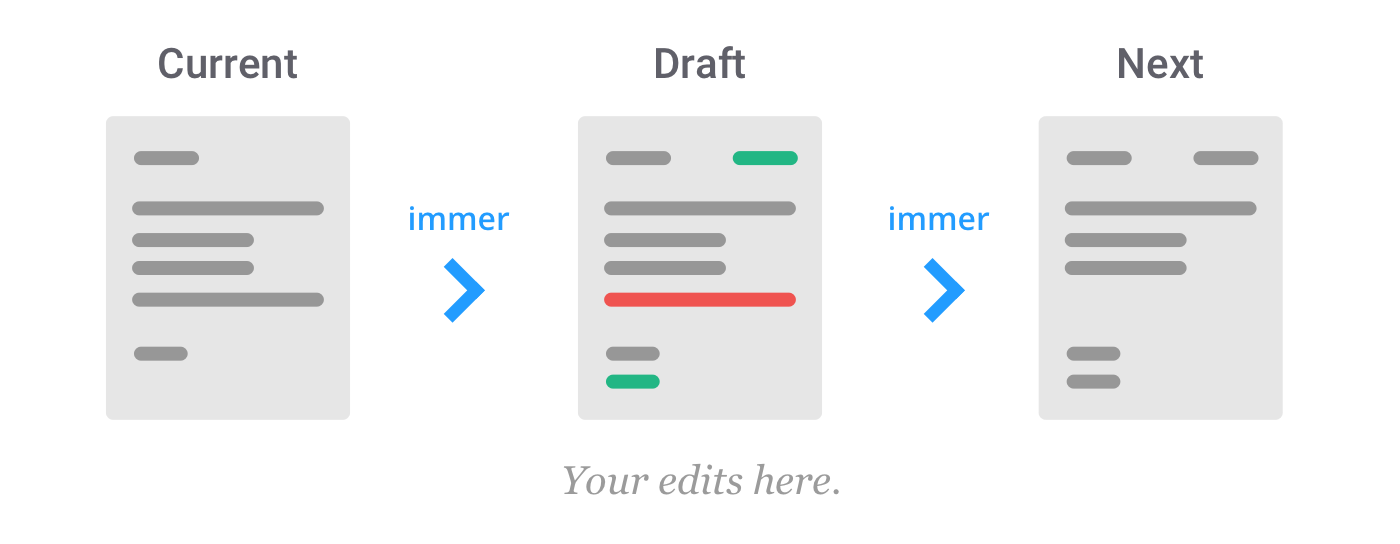

Very often, state is stored in objects and arrays, and the convenience of mutability seems enticing, especially when it reduces lines of code and makes them more understandable. Luckily, there are a few tools that allow us to "mutate" immutable state objects in very specific circumstances (namely the Immer library).

The Immer library is a small package that allows updates to look mutable, while still enforcing immutable state changes. Immer is built into other React tools like Redux and the use-immer package, both of which we will discuss throughout this course.

Updating Objects in State

Objects in state can be updated a number of ways, but the most common is through the use of the spread operator. The spread operator allows us to make shallow copies of objects and arrays, which is necessary for updating state in React. We cannot update the existing state object, but we can copy it, makes changes to the copy, and then set the new state to that copy.

As a reminder of how JavaScript handles object properties, examine the following code:

const myObj = {

learning: true,

confidence: 9.7,

confidence: 9

}What is the value of myObj.confidence?

Since keys in JavaScript objects are unique, there can only be one final value when multiple keys of the same name are given.

Using this behavior, we can copy and update entire objects very easily. Take the following example:

userState = {

isLoggedIn: true,

status: "hidden",

content: null,

active: true

}If we wanted to update the user's status to "visible", would this work?

userState.status = "visible";

setUserState(userState);It would not, because the userState reference remains the same, and React does not know that anything changed to make an update.

Instead, we could use the spread operator to create and modify a copy of the current state:

setUserState((userState) => {

...userState,

status: "visible"

});This effectively overwrites the status within the copy of userState, passing a new state reference and triggering an update!

Below is a more visual example from the React documentation. In this example, the red dot is supposed to follow your mouse cursor while it is within the preview area. If you examine the code, you can identify why this does not work as intended.

Modify the onPointerMove attribute to use the setPosition state setting function and pass it a new state object with the appropriate values.

Note that there are a few ways of going about this, and while state mutation is not okay, local mutation is perfectly fine. For example, our previous userState example could look like this instead:

const nextUserState = { ...userState };

nextUserState.status = "visible";

setUserState(nextUserState);We can mutate nextUserState as much as we would like to until it becomes a part of state, because no other code is referencing it yet. As soon as it becomes a part of state, all code that references that state needs to know when updates occur.

Let's look at another example that uses a state object to hold and update information stored in multiple form fields, again adapted from the React documentation:

This is a very common pattern for form building in React, which binds each form input to an onChange listener. This is one of two parts of a "controlled form," which we will discuss more in future lessons.

Currently, the form does not work as intended. If you attempt to update any of the inputs, you will find that they cannot change! This is due to the current onChange handlers, which attempt to mutate the state and do not call setPerson. We can fix this in one of two ways:

- Copy the individual state values and update the state object with the new input value:

setPerson({

firstName: e.target.value,

lastName: person.lastName,

email: person.email

});- Use the object spread syntax and update the state obejct with the new input value:

setPerson({

...person,

firstName: e.target.value

})Try updating the onChange handlers to get the form to work properly.

Take note of the way the entire form's data was stored in one state object, rather than individual state objects per input. As forms get larger, it is very convenient to keep all of the form's data kept in a single object, as long as you update it correctly.

There is one other useful JavaScript technique that can simplify this process: object properties can be set and referenced using variables! This means that as long as our form name attributes and our state object properties are identical, we can use a single event handler to handle all of our input events, like so:

function handleChange(e) {

setPerson({

...person,

[e.target.name]: e.target.value

});

}Try updating the sandbox example to use this function for every input element, and verify it works.

Updating Nested State Objects

While the spread operator is useful, it must be used multiple times to handle nested objects in state.

If we had a more complex person state that also stored address information, it might look like this:

const [person, setPerson] = useState({

firstName: "S'Chn T'Gai",

lastName: "Spock",

email: "spock@ussenterprise.space",

address: {

city: "USS Enterprise",

state: "Where No Man Has Gone Before",

zip: "9083147"

}

});When updating this state, we could not use our simple spread pattern:

setPerson({

...person,

address.zip = "9083177";

});The reference to the address object is still the same, so React will not notice an update!

In order to overcome this, we need to spread both objects:

setPerson({

...person,

address: {

...address,

address.zip = "9083177";

}

});As you could imagine, this will get rather wordy with large, multi-tiered state objects. In general, if your state is deeply nested you might want to consider flattening it; however, if you don't want to make changes to the state's structure, you might want to look into Immer, which allows you to "break the rules" of mutating state without actually breaking the rules.

We'll talk about Immer after discussing arrays in state.

Updating Arrays in State

Just like with objects, arrays in state are to be considered immutable. Many of the same techniques used on objects, such as the spread operator, can be used on arrays. Unlike objects, however, arrays do not have unique keys that can be used to easily overwrite their data. Also unlike objects, arrays come with a number of methods that already perform immutable changes to the array by returning a new array instead of modifying the existing one in place.

The following array methods mutate the original array, and therefore cannot be used to set state:

- adding:

push,unshift - removing:

pop,shift,splice - replacing:

splice,arr[i]assignment - sorting:

reverse,sort

These methods can be used, since they return a new array:

- adding:

concat,[...arr]spread syntax - removing:

filter,slice - replacing:

map - sorting: make a copy of the array first

With Immer, you can use all of these array methods, not just the ones that return new arrays.

Adding to an array is most commonly accomplished by using the spread syntax and either appending or prepending the new value:

setPeople([ // Replace the current state with a new array

"Patrick", // Prepend values before copying the old values

...people, // Copy all of the old array values

"Sandy", // Append values after copying the old values

])In this way, you can use the spread syntax to accomplish the same tasks as push and unshift, all without mutating the original array. This technique can also be useful outside of the context of React state, so keep it in mind for other applications!

Removing items from an array can be accomplished by filtering those items out. Take a look at the following example from the React documentation, which uses map to create a list of artists from the artists state array, and then creates a button with an onClick listener that uses filter to remove the artist from the state list.

Since filter returns a new array, we can use it to directly set a new state and trigger updates.

Transforming an array is similarly accomplished using the map method. Like filter, map returns a new array and can be used to directly update state. If you need a refresher on the map method, check the MDN documentation; there is nothing unique about its usage with React (good JavaScript knowledge really pays off with React!).

Replacing items in an array is one of the most common "mutations" that will need to be accomplished when dealing with state arrays, and can also be accomplished with map.

Here is an example of map accomplishing both a transformation and a replacement. When the "Increment" button is clicked, it adds one to the state value of the counter at the given list index (transformation), and sets all other list index values to 0 (replacement).

Inserting into an array can be slightly daunting, but there is a simple pattern using slice that can be adapted to most situations:

- Take a

sliceof a copy of the original array using the spread operator, up to the point of insertion. - Insert the new data into the array after the slice.

- Take a second

sliceof a copy of the original array using the spread operator, from the point of insertion to the end of the original array.

Here's how that looks, packaged into a reusable function. Save this somewhere, or remember this pattern, so that you can adapt it for your own purposes in the future!

function immutableInsert(arr, newItem, insertAt) {

const nextArr = [

// Items in the original array before the insertion point:

...arr.slice(0, insertAt),

// The new item being added:

newItem,

// Items in the original array after the insertion point:

...arr.slice(insertAt)

];

// Return a new array.

return nextArr;

}Making other changes to a state array like sorting can be accomplished simply by creating a copy of the array using spread syntax before mutating it and setting the newly mutated copy as state.

Aside: Objects inside of State Arrays

Just like with nested state objects, objects within state arrays must also be treated as immutable. The same spread operator patterns that work for nested objects work for objects within arrays.

The useImmer Hook

The use-immer package, installed with npm install use-immer, contains the useImmer hook:

import { useImmer } from "use-immer";The useImmer hook allows us to use the power of the Immer library to write mutating state functions without breaking React. It directly replaces the useState hook, allowing you to continue with familiar syntax but with fewer restrictions.

Before we show you how useImmer works in practice, let's touch briefly on how Immer itself works behind the scenes.

Here's what the Immer documentation has to say about the topic:

"The basic idea is that with Immer you will apply all your changes to a temporary draft, which is a proxy of the currentState. Once all your mutations are completed, Immer will produce the nextState based on the mutations to the draft state. This means that you can interact with your data by simply modifying it while keeping all the benefits of immutable data."

"Using Immer is like having a personal assistant. The assistant takes a letter (the current state) and gives you a copy (draft) to jot changes onto. Once you are done, the assistant will take your draft and produce the real immutable, final letter for you (the next state)."

Like most pre-packaged solutions, Immer is slightly less efficient than a custom-tailored solution could be. However, in practice, Immer will often save you more time and processing power than attempting to develop a custom solution would, making it widely considered the best solution for handling immutability. If you are ever curious about the performance differences, you can look into this benchmark test.

To understand the simplicity of Immer, let's revisit one of our previous examples:

In this example, useState has been replaced with useImmer, and we were able to use forEach to mutate individual array elements directly, rather than using map to build a new array. We are able to do this because the c being passed into setCounters is no longer the original counters state, like it would be with setState; it is a draft state created by Immer for us to be able to mutate. Because of this, you will often see the state variable in Immer set functions named draft.

Likewise, you may often see useImmer functions named updateState instead of setState, to more accurately describe how they behave and to differentiate Immer from React's default state management.

The very simple example above does not quite demonstrate how powerful and convenient this functionality can be. In order to emphasize this, let's look into a more complex example.

Below, we have a state array persons that contains person objects which each have name objects, address objects, and contact objects. The address objects also contain another object, billing, for storing billing addresses that are separate from mailing addresses. To save space, we've only included one entry in this array, but imagine it contains several dozen or more.

Modifying a single piece of state in this particular case can become quite cumbersome, as shown.

const [persons, setPersons] = useState([

{

id: 1,

name: {

first: "Bilbo",

MI: null,

last: "Baggins"

},

address: {

line1: "Bag End",

line2: "Bagshot Row",

city: "Hobbiton",

state: "The Shire",

zip: "327814"

billing: {

line1: "Bag End",

line2: "Bagshot Row",

city: "Hobbiton",

state: "The Shire",

zip: "327814"

}

},

contact: {

email: "bilbobaggins@theshire.hob",

phone: "555-555-0110"

}

}

// ... many more entries

]);

function handleChange() {

// Shallow clone the persons array:

const newState = [...persons];

newState[0] = {

// Replace the element to be modified with a shallow copy of itself:

...newState[0],

// Shallow copy all the way down to our desired change:

address: {

...newState[0].address,

billing: {

...newState[0].billing,

zip: "327777"

}

}

};

setPersons(newState);

}As you can imagine, it may get very difficult to keep track of where you are and what you've done when using this syntax.

It is important to understand how to handle complex state operations with useState, because there are situation in which you may encounter it in legacy code or in applications that simply choose not to use Immer for one reason or another.

That said, here's how useImmer could change our handleChange function:

const [persons, setPersons] = useImmer([

// ... many entries

]);

function handleChange() {

setPersons((draft) => {

draft[0].address.billing.zip = "327777";

});

}Much cleaner, and much easier to understand.

We will continue to talk about the power of Immer when we cover reducer functions, the useReducer hook, and Redux. We will also build upon the lessons learned here in the next couple of lessons, which will introduce the concept of "thinking in React" and expand upon creating interactive features within a React application.

Rendering Arrays from State

R-ALAB 320H.3.1 - Rendering Arrays in React will have you put together a simple application that renders an array stored in state.

Please complete this lab activity, and follow the submission instructions included within.